Here’s a story I ran across while researching one of the walks for our next book, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? Roundups & Executions. It’s one of those long-lost facts about Paris that has slipped into the historical fogbank. I don’t know how many past or present French teachers read my blogs, but I think I will go out on a limb here. I’ll bet most French teachers aren’t aware of the major slum once located in the middle of historic Paris (2e) called la cour des miracles. If they could squeeze their students into Dr. Who’s time travelling space ship, dial back to 16th- or 17th-century Paris, and set course for a large area now bounded by four contemporary streets, the time travelers would find themselves in the middle of a dangerous community of thieves, beggars, prostitutes, and murderers. Before you leave, I would recommend you arrive during the day.

Did You Know?

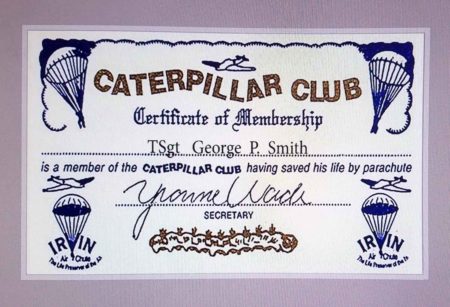

Did you know that there is an organization called the Caterpillar Club? No, it’s not a country club for the executives of Caterpillar, Inc. It’s an association of people who have successfully deployed a parachute to bail out of a disabled aircraft. The informal club is maintained by Airborne Systems (click here), a manufacturer of parachutes. If an applicant’s experience is authenticated, they are issued a certificate and silver pin. The nationality, ownership of aircraft, or other factors are immaterial⏤only the fact that the person’s life was saved by using a parachute is what matters. (Oh, one other factor does matter: the aircraft had to have been disabled naturally, including being shot down.)

The founder of the club in 1922, Leslie Irvin, named it after silk threads that were used to make the original parachutes. The silver pins are in the shape of the silkworm, or caterpillar. The club’s motto is “Life depends on a silken thread.” By the end of World War II, about 34,000 people were members. Some of the aviator members include Gen. Jimmy Doolittle, Charles Lindbergh, and John Glenn. The first female member was Irene McFarland in 1925.

Many thanks to Greg Smith for supplying the images of his father’s certificate, membership card, and silver pin. T/Sgt George P. Smith (1920−1983) was the left waist gunner on a B-17 shot down in May 1943 over France. (click here to read the blog Rendezvous with the Gestapo)

Paris Building Periods

During the late 12th- and early 13th-centuries, King Philippe II Auguste constructed the first city wall surrounding Paris (both right and left banks) for the purpose of repelling attacks on the city. As the city expanded, King Charles V built a new wall on the right bank in 1566. By 1670, Louis XIV declared the city safe enough from outside attacks that he ordered the demolition of the walls. With or without a wall, 17th-century Paris was still a medieval town and dangerous. The streets were narrow and dark, the city was very noisy and congested, it smelled, and walking the streets, especially at night, put you in harm’s way. The houses were primarily constructed of wood, multi-storied but small, and sewage was disposed of by throwing it out into the middle of the street. Streets didn’t have names and there were no maps, so it was easy to get lost⏤everyone pretty much stayed in their own neighborhoods. There were no sidewalks or curbs so being run over by horses pulling a carriage was a potential hazard. Another reason not to venture far from home was the fear of being assaulted, robbed, or murdered by roving criminals. Yet, attacks by feral animals (e.g., wild boars) that roamed the streets were responsible for a majority of deaths.

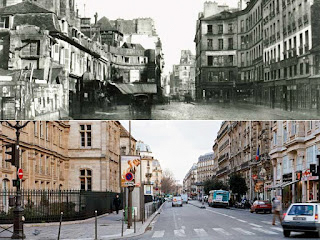

There were three primary building periods in Paris: seventeenth century, mid-19th century, and the 1970s. The mid-19th century was marked by the Second Empire of Napoléon III. He hired Baron Haussmann to transform Paris into the modern city we enjoy today. During the 1970s, like many governments around the world at the time, Paris underwent urban renewal and its “out with the old and in with the new” brought many changes. President Georges Pompidou spearheaded the replacement of older buildings (e.g., Les Halles) with newer and modern structures (e.g., an underground Les Halles and the Pompidou Center).

It is the 17th-century we will concentrate on in today’s blog. Paris wouldn’t shed its medieval cloak until Haussmann’s renovations two hundred years later. Up until the 17th-century, building or improvements were strictly carried out by the king. However, by the mid-17th-century as the city grew and stratification of French society took hold, wealthy Parisians began to build grand maisons (i.e., homes or mansions). Most of these 17th-century maisons are now government offices, apartment buildings, or hotels.

Parisian Society

Paris’s population went from around 300,000 in 1600 to about a half million in 1680. The structure of Paris society was very rigid. At the top of the heap (but below the royals) were the nobles. Known as personnes de qualité, or “quality people,” the nobility did not work. Their wealth was concentrated in real property. The titles of duke, marquis, comte (i.e., count), or baron were derived either by birth or granted by the king. The nobility, or second estate, did not pay taxes and by 1789, that would come around to bite them in their collective noble rear ends.

Below the nobility were the “Notables.” These were senior officials in the government, royal accountants, and a few prominent doctors and artists. Just below the Notables, was the Maîtres class consisting of lawyers, notaries, and junior government officials. One of the largest classes was the Bourgeoisie, or middle class. It was a burgeoning social class and consisted of successful merchants, artisans, and craftsmen. While the middle class had cash, they did not possess the vast amounts of land or buildings that the nobility and notables used as a measure of wealth.

The class below the Bourgeoisie comprised the largest single group of Parisians. These were the domestic servants, manual laborers with no appreciable skills, street vendors, and other occupations that provided a meager living.

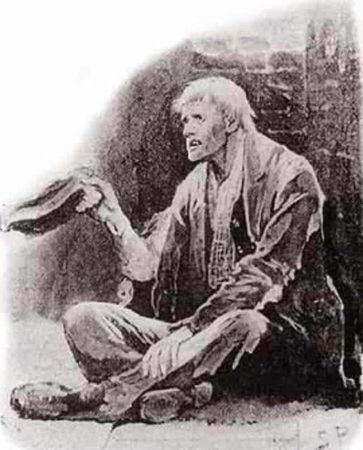

The people at the lowest rung of society were the beggars, prostitutes, vagabonds (i.e., those who came to Paris from rural towns looking for work) and the poor. Much like how we struggle today with issues facing the homeless, Paris decided the forty thousand mendicants, or beggars had to be dealt with. If someone could not prove they were born in the city, they were kicked out of Paris. The others were put to work. All sorts of different types of programs were devised but by 1615, these well-intended but flawed programs failed. The beggars returned to the streets and along with the thieves, began to develop highly organized slums.

Court of Miracles

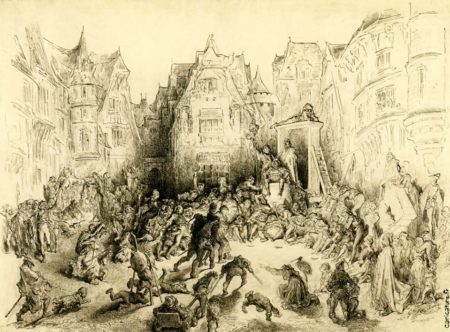

By the mid-1400s, the population of Paris was around 250,000 of which eighty thousand were beggars. The number of different types of criminals was staggering. One hundred years later, crime had risen to levels never before seen in the city. In fact, it was so bad that the government saw the problem as a threat to the king, his ministers, and the city government. A criminal group once attacked Les Halles market and killed the city executioner. One of the ports on the Seine was destroyed and in 1534, a gang broke into the Louvre and stole the king’s royal flag. Right around that time, groups of thieves, beggars, and prostitutes began forming small, secret enclaves around the city where they could retreat each night.

Slums have always existed in Paris and its suburbs. Merriam-Webster defines a slum as “a densely populated usually urban area marked by crowding, run-down housing, poverty, and social disorganization.” One of the major slum areas in 17th-century Paris met this definition except for one aspect: social disorganization.

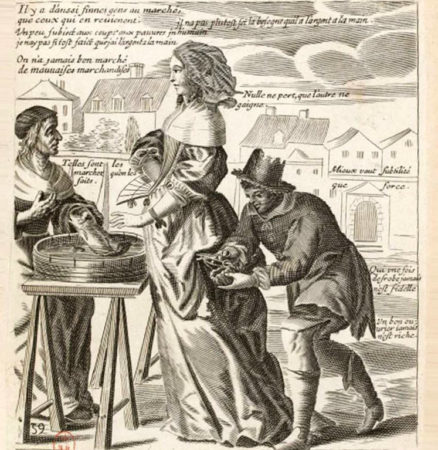

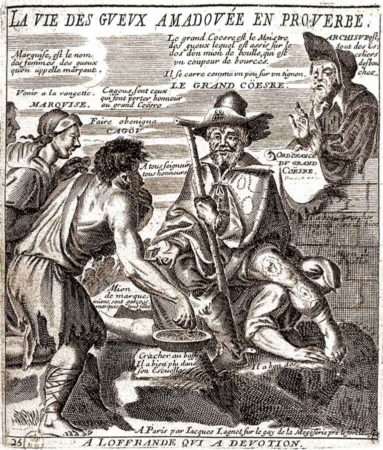

The twelve principal Paris slums were called la cour des miracles, or “Court of Miracles” because the beggars, hustlers, and thieves would return each evening miraculously cured of their afflictions. Their fake blindness, amputations, and illnesses were suddenly cast aside until the next morning when they went back out into the city searching for their next prey.

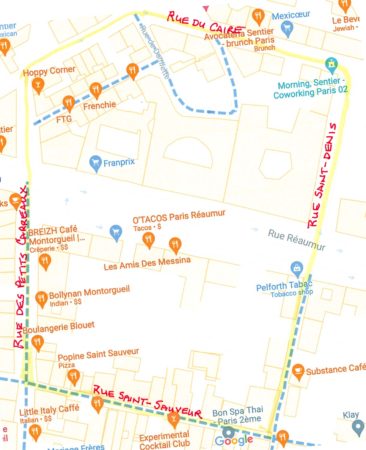

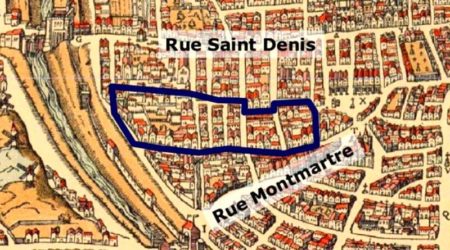

The largest and most dangerous cour des miracles dated back to the thirteenth century and was situated in what is today the second district. Bounded by the contemporary streets rue Saint-Sauveur to the south, rue des Petits Carreaux to the west, rue Saint-Denis on the east, and to the north, rue de Caire, la cour des miracles was organized into a social stratum ruled by the King of Thieves known as the “Great Chief.” The king had his lieutenants known as cagoux or Ducs who instructed newcomers in the ways of their society.

The Great Chief watched over his “subjects” and collected a percentage of each person’s daily take. These cash tributes were called cracher dans le bassine, or “spitting in the basin.” The rule was that any money left in one’s pocket after payment was to be spent that evening on drink and prostitutes. The king was easy to spot⏤he wore a bonnet, a torn sheet, and carried a scepter. This aberrant community had its own laws, officers, and ceremonies. Children were taught at a young age how to beg and steal in addition to simulating blindness, illness, and a wide range of injuries. There were formal schools set up around the city to train people in robbery and prostitution.

The social strata was well-defined especially with respect to a strict hierarchy of criminal activity. The community had its own language (i.e., slang) and rules of conduct. Each discipline (i.e., thieves, beggars, etc.) was considered to be a “Guild.” The courtauds de boutanche, or part-time beggars were only allowed to work the streets in the winter. Les capons worked the cabarets as pickpockets while the Millards were the pickpockets who stole provisions. Les francs-mitoux faked illness so well that they fooled the best doctors. Les hubins held fake certificates stating they had been cured of rabies and needed money for their pilgrimage to thank Saint Hubert. Les rifodés were men who, accompanied by their wife and children, presented a fake certificate confirming their house had been burned down and they needed money to rebuild. The Sabouteux faked violent epileptic seizures while frothing at the mouth (using soap). The piètres were the false cripples. The coupeur de bourse were the “purse cutters” and in order to join their guild of thieves, the new person was required to perform a robbery in plain sight of the other robbers. If the initiation went according to plan, a new member was accepted. If it didn’t, well . . .

La cour des miracles was featured in the Victor Hugo’s book, Notre-Dame de Paris (i.e., The Hunchback of Notre-Dame). The area had a strong smell and was accessible only by traveling through very narrow and tiny streets. The area was dark and eerie. Very little sunlight made it to the ground.

Henri Sauval (1623−1679), a French historian, once ventured into la cour des miracles (with a bodyguard of course) and described his impressions:

“This courtyard is situated in a square of some considerable size and in a stinking cul-de-sac. To get there you must find your way through tiny and foul streets, which twist and turn in all directions; to get into the square, you must stumble down a quite long and uneven slope. I saw there a half-buried house of mud, strikingly old and rotten, of no more than fifty square yards, but which lodged fifty women in charge of an infinite number of infants, naked or half-dressed. I was told that five hundred families, piled on top of one another, lived in the courtyard. It had been bigger in the past; nowadays, one was nourished by idleness, grew fat on brigandry, in greed and all sorts of crimes and vice. There, with no thought of the future, each enjoyed the present and ate each evening with pleasure that which had been acquired with so much trouble to others and even violence during the day; for there to earn was to rob; and it was one of the fundamental laws of the cour des miracles that nothing should be kept for tomorrow. Each person lived great license; there was neither faith nor law. Baptism, marriage, and sacrament were unheard of . . .”

Court of Miracles Laws

There were some hard and fast laws that the inhabitants of la cour des miracles were required to follow. Here are a few of them.

- All the Wretched are equal before the Miracle Court.

- All the Wretched are free; slavery is forbidden.

- Keep to your Guild for protection and strength.

- Physical attack on a member of another Guild is considered an act of war.

- You must have permission to enter other Guild houses.

- Keep the laws, or punishment will be swift and certain.

Disabled beggars. Illustration by anonymous (date unknown). Wikimedia.

Clearance

By the mid-17th-century, Paris had had enough of the denizens of la cours des miracles. Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie (1625−1709) was hired in 1667 as the first police chief to lead the new Préfecture de police in Paris. Reynie’s first task was to put a halt to rampant crime in the city. He started by demolishing the slums and the first slum he chose to “rehabilitate” was the one ruled by the King of Thieves. The police chief’s men stormed la cour des miracles and tore down the buildings. It is said that he threatened to hang the last twelve people found alive in the area. At that time, about five hundred families lived in the cour des miracles. The site was divided up into lots and sold to developers. However, the area had such a bad reputation that people refused to venture into the former slums. (Today, the area is known as the Bonne-Nouvelle quarter.) It wasn’t until the mid-19th-century and Haussmann’s renovation that all the inner-city slums were eliminated. Unfortunately, they only relocated.

★ Learn More About the Court of Miracles ★

Grant, Kester. The Court of Miracles. New York: Ember, 2020.

Hussey, Andrew. Paris: The Secret History. London: Penguin Books, 2006. Pages 125-127.

Jones, Colin. Paris: A Biography of a City. New York: Penguin Books, 2006.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Well, I’m pleased to announce we are the proud parents of a new one pound, eight ounce book. We received our boxes of books several days ago and Sandy has activated the Amazon page (click here) so people can purchase the book online. Amazon may indicate that the book is currently unavailable. We are working with Amazon to get the inventory replenished, we have plenty of books!

However, you do have another purchase option other than Amazon. If you contact Sandy (sandy.ross@yooperpublications.com) and let her know you’d like to purchase a book, she will make arrangements to get one to you. We will pay domestic postage and I will autograph the book with a personal note. For our friends overseas, postage is on you, but the book will be autographed. Unfortunately, we cannot send any books into France. The government is trying to protect their independent bookstores (can’t say I blame them).

Thank you to everyone who has expressed an interest in the publication date and has waited patiently for this day to arrive. It took a little longer than we anticipated to get to this point. The first draft of Volume Two is about seventy percent complete so I don’t expect to have the same delays.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Martin Dwight B. for contacting us regarding the blogs. Martin liked the blogs so well that he has recommended our web site to relatives, friends, and others who share an interest in history. Martin mentioned that his father was a great admirer of Dwight D. Eisenhower (ergo Martin’s middle name). Thanks again Martin for reaching out to us, subscribing to the bi-weekly blogs, and referring us on to your friends.

I’d also like to thank Steven for alerting us to a mistake I made in the blog, Diplomatic Lessons and Warning Signs (click here to read the blog). One of the maps incorrectly reflected the location of the Sudetenland. We replaced the image in the blog with a correct map and caption. Not much gets through after our numerous edits and reviews but in this case, it did. I always appreciate our readers getting in touch with me when they notice a mistake. (This wasn’t the first time nor do I suspect it will be the last.)

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross

Another missing piece of the puzzle comes to light. Thanks for giving us a fascinating tour of 15th century Paris, Stew. The best and worst of humanity live on. The only difference today is that the rich never walk the streets and they always remain out of sight. Regards…Greg

Thanks Greg. I guess that’s why they call it “hidden wealth.” STEW